Nigeria is an established oil producer grappling with declining market share and dimming economic prospects – but it could reverse its fortunes if authorities take a proactive approach to exploration and export, namely for natural gas.

The country has the second-largest proven oil reserves in Africa, after Libya. It sits on the 10th-largest proven oil reserves in the world, with roughly 2 percent of global reserves behind Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Russia, the United States and Libya. It is also the oldest sub-Saharan OPEC member country, having joined the producer group in 1971.

Reserves, production and options for the future

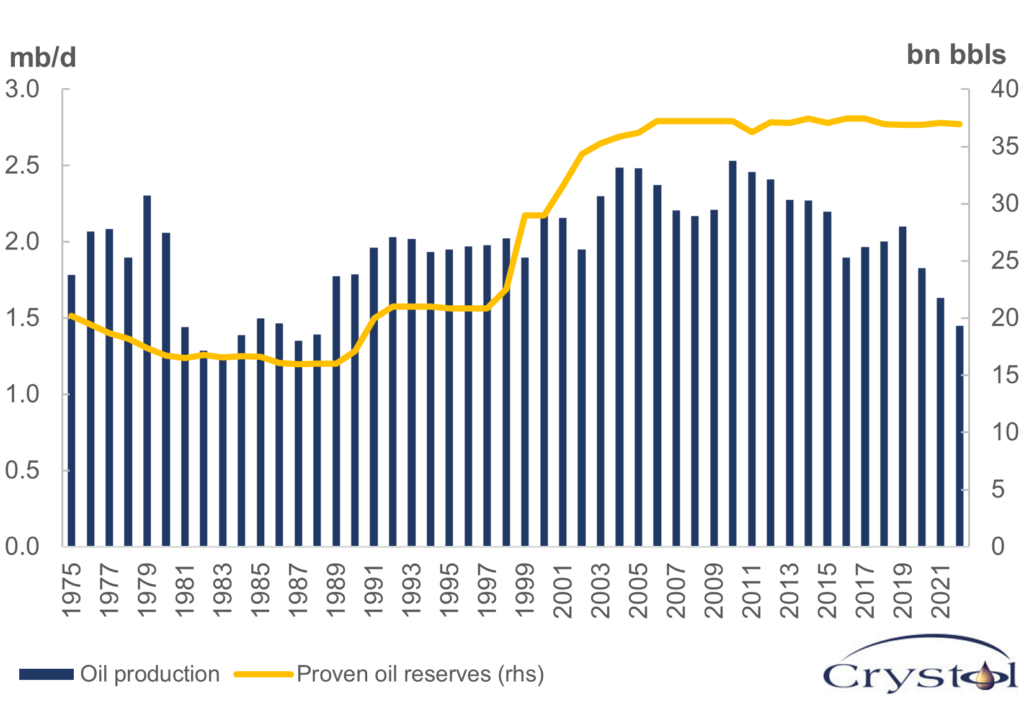

Nigeria dominated Africa's oil production for 42 years (1979-2021). At its prime in 2010, its production reached 2.5 million barrels per day – equivalent to more than a quarter of the continent’s total output. However, since that peak, due to difficult investment and security environments and producers exiting the country, Nigeria’s oil production has experienced one of the fastest declines in Africa, shrinking at an average annual rate of 5 percent from 2012 to 2022, when Nigeria produced 1 million barrels per day less than its peak volume. That decrease is equivalent to the total oil production of Angola, the second-largest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa. Today, Nigeria is the 16th-largest oil producer in the world.

A loss in production spells trouble for this oil-dependent economy. According to the International Monetary Fund, since Nigeria became a significant oil producer in the 1970s, hydrocarbon products have consistently accounted for 90 percent of its exports. In 2023, Abuja announced an ambitious plan to return to growth and surpass historic peak production levels with a new target of 2.6 million barrels per day by 2026. This would translate into a massive increase of 79 percent in just two years (more than adding another Angola-sized producer to global output).

But for a country that has been struggling to meet its production quotas even within OPEC, it is not easy to imagine where this transformation will come from, especially when major energy companies are ending decades-long relationships in Nigeria because of the challenging investment climate. The industry and leading international organizations do not share the government’s enthusiasm or rosy growth outlook. According to some estimates, oil production in Nigeria could still decline by another 35 percent over this decade if investment in key fields is not undertaken. Similarly, according to the International Energy Agency, Nigeria’s crude oil production capacity is expected to shrink to 1.1 million barrels per day by 2028.

Nigeria’s proven oil reserves have plateaued in recent years, but this by no means indicates that Nigeria is running out of opportunities; on the contrary, its deepwater potential largely remains untapped. The necessary exploration and development of such resources, however, will be neither cheap nor fast.

Additionally, in a more climate-conscious world, a solution that could deliver sustained economic growth would be for Nigeria to capitalize on low-hanging fruit – that is, natural gas. Gas has the potential to transform the country’s future role in global energy markets should above-ground factors, particularly government policy, provide the necessary prerequisites for the sustainable exploitation of the resource.

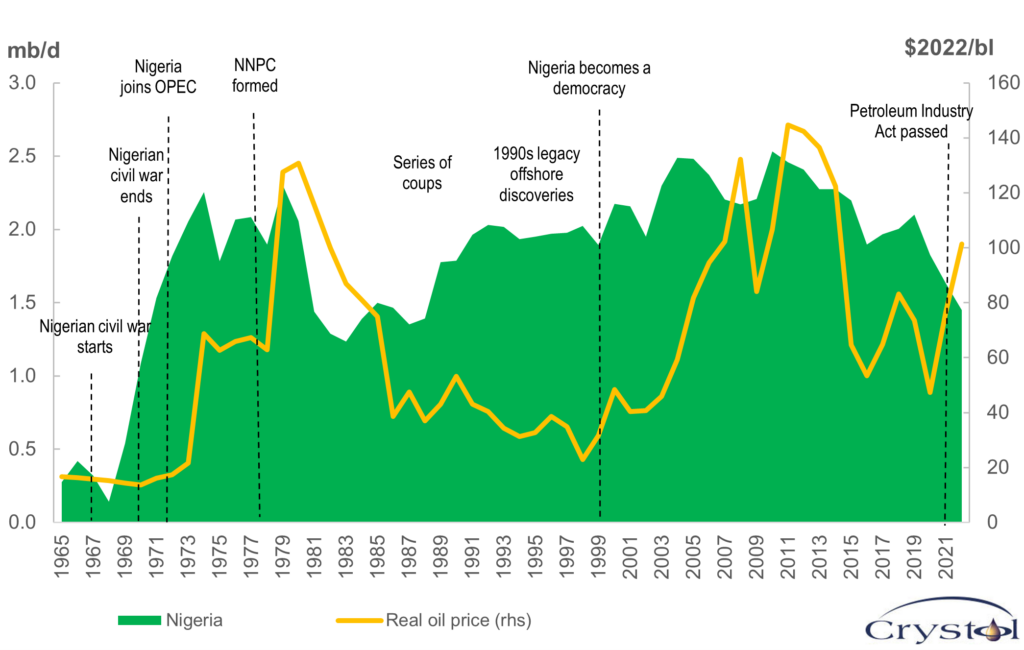

Oil and politics

Following a brutal civil war that ended in 1970, oil activity temporarily boomed in Nigeria amid a period of rapid growth in worldwide oil demand while nearly half of global production was concentrated in OPEC countries. But it was Nigeria’s turbulent political environment that soon ended the first oil boom. In the roughly two decades after the civil war, six coup attempts took place in Nigeria, four of which were successful in overturning the previous rulers. The related decline in exploration activity resulted in shrinking reserves and falling production. Between 1974 and 1989, the country’s proven oil reserves decreased by nearly 2 percent annually.

After the last coup in 1993, the political environment in Nigeria at last stabilized. By 1999, the country had transitioned from military to democratic rule, delivering confidence to international investors and resulting in increased exploration activity for both oil and gas – with particular interest in the latter. Also, in the 1990s, several important discoveries occurred that significantly increased the country’s hydrocarbon reserves base, including major finds in waters at depths of more than 1,000 meters. The developments were facilitated by improvements in technology and higher market prices, justifying the costs of exploration and extraction in such offshore fields.

Nigeria’s oil production vs. oil price

Source: Energy Institute

New wave of declines amid few new discoveries, rising U.S. shale output

By the mid-2000s, most of those discoveries had converted to production, fueling strong growth. However, after peaking in 2010 and despite oil prices hovering around $110 per barrel for three consecutive years (2011-2013), production in the last decade began to decline again, given a lack of further discoveries and investment. Nigeria’s ongoing slide in output has been so pronounced in recent years that the country has been unable to reach its OPEC quota.

The negative trend in production came as the shale revolution took off in the U.S., which fundamentally altered oil market dynamics. The U.S., historically one of the main buyers of Nigerian oil, became a tough competitor, especially as U.S. and Nigerian crude share similar characteristics and therefore target the same markets.

Why oil majors are divesting

Several factors have driven Nigeria’s current oil production decline. Chief among them is the poor investment climate due to a combination of security risk and unfavorable policies.

The majority of Nigeria’s oil production comes from onshore fields – particularly in the country’s Southern Niger Delta – which are more vulnerable than offshore production to acts of sabotage and terrorism. According to the Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative, around 15 percent of crude oil production has been lost due to theft or errors in production metering.

The most notable incident related to pipeline theft was the 2009 crisis when militants targeted onshore pipeline infrastructure. The large-scale disruption was resolved after a presidential amnesty program was launched, whereby armed youths could surrender their weapons to the government in return for amnesty, training, and rehabilitation. That, however, did not end hostilities.

More recently, in 2023, an explosion in one of the oil pipelines owned by Shell resulted in the deaths of 12 people. That and similar attacks have been deciding factors leading oil majors to exit the country or focus on offshore operations. Such divestments have happened despite the relatively high oil price environment, conveying a general lack of confidence in Nigeria’s oil sector, at least onshore.

While Nigeria is estimated to hold the world’s largest remaining crude oil and condensate deepwater reserves in the world and the third-largest ultra-deepwater reserves (after Brazil, the U.S., and Angola), the exploitation of those riches is costly. The economics could be improved if Abuja offered more attractive fiscal terms and contractual arrangements.

However, despite enacting new policies in recent years to support oil investment, Nigeria’s practices are not conducive to attracting investors to the opportunities. Additionally, the slow implementation of policy reforms only exacerbates the situation; the Petroleum Industry Act, which aimed at reforming the country’s upstream sector, took 13 years to pass after it was initially proposed in 2008.

Nigerian oil production and reserves

Source: OPEC, Energy Institute

Natural gas: Light at the end of the tunnel

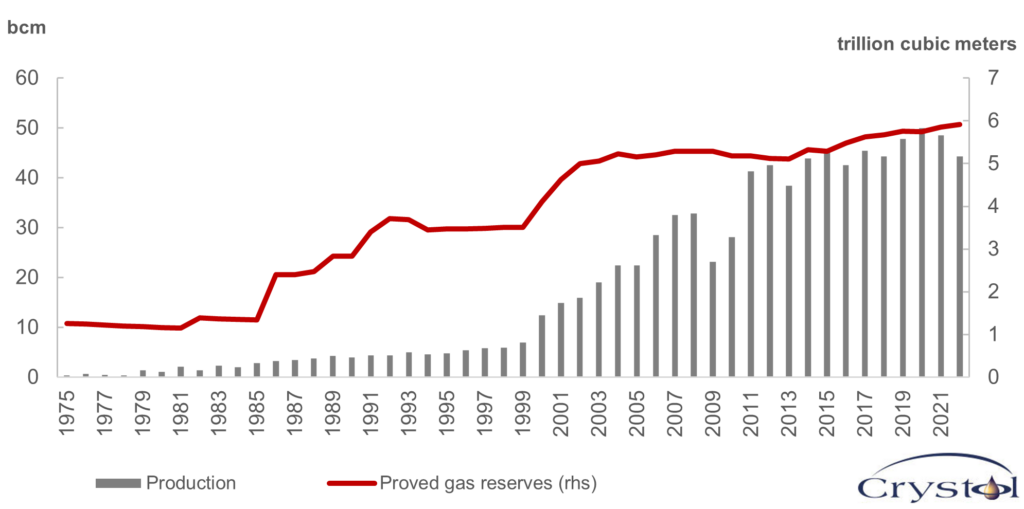

Within this rather gloomy picture resides an attractive opportunity in light of domestic priorities and global trends: natural gas. In Nigeria, the gas sector has shown greater resilience than oil, particularly non-associated gas, which is produced independently of oil. Nearly half of Nigeria’s gas production is non-associated.

Nigerian gas production and reserves

Source: OPEC

Nigeria holds Africa’s largest gas reserves and is the continent’s third-largest producer after Algeria and Egypt. Globally, its reserves rank eighth (after Russia, Iran, Qatar, the U.S., Turkmenistan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE), but its production is only 18th. Gas reserves, however, have been steadily increasing, as has production. Between 2000 and 2022, Nigeria ramped up its gas production by an impressive 260 percent by adding nearly 30 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas to its production. In the same period, Algeria boosted its output only by 7 percent, adding just 6 bcm.

Although Nigeria had become notorious for its gas flaring – burning the gas associated with oil production (associated gas) – the country has made significant progress in reducing this environmentally harmful and economically wasteful practice. Between 2012 and 2022, Nigerian gas flaring decreased by nearly 45 percent. To be sure, it is unclear how much of that progress is the result of the enforcement of more responsible regulations or due to the decline in oil production (which decreased by 40 percent over the same period).

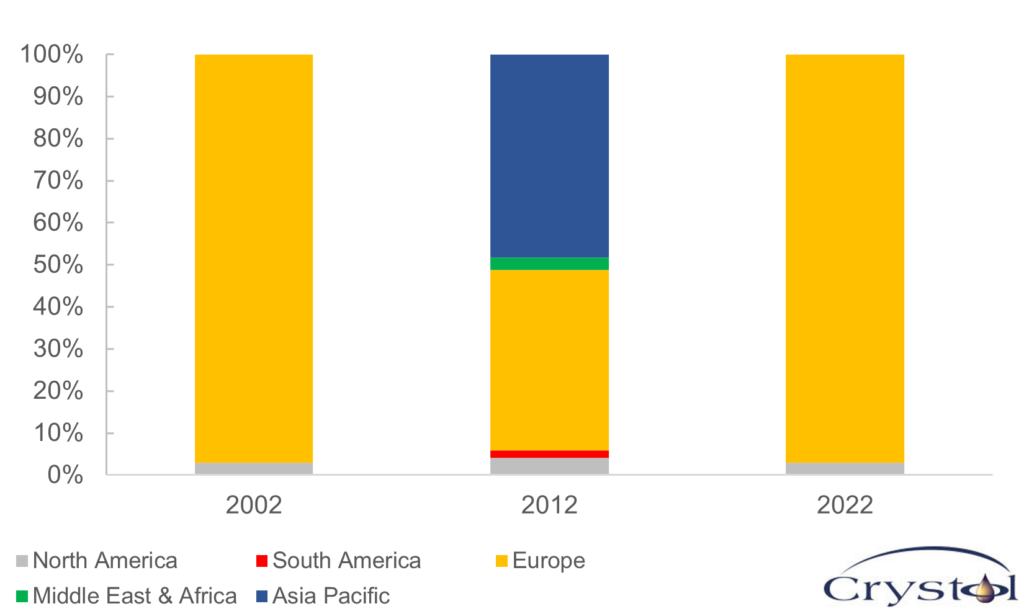

Nigeria accounts for 36 percent of Africa’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports, making it the continent’s leader. With a 3.6 percent share of world LNG exports, Nigeria ranks sixth globally, only behind Qatar, the U.S., Australia, Russia, and Malaysia. In 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and European Union member states subsequently slashing imports of Russian gas, the European market began to absorb nearly all of Nigeria’s LNG exports.

Nigerian LNG exports by destination

Source: BP, Energy Institute

Abuja is keen on developing the sector further, but results to date have been mixed. In 2008, it launched the Gas Master Plan, aiming to establish Nigeria as a natural gas hub for supply and demand by 2015, but those targets were not met. In 2017, the government initiated a more modest Natural Gas Policy.

The most recent policy initiative, announced in 2021, declared the 2020s as the “decade of gas – towards a gas-powered economy” for Nigeria. The ambitious plan aims to reach the unachieved targets of previous initiatives, and calls for the construction of two major gas pipelines. The first is the Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline, which aims to export gas from Nigeria via Algeria to Europe. The second is the African-Atlantic Gas Pipeline, an extension of the West African gas pipeline that envisions exports of gas to Europe via Morocco while passing through the exclusive economic zones of 13 African countries. An expansion of Nigeria’s LNG export capacity is also among the options to restore growth.

Scenarios

Nigeria needs to act on at least one of its export initiatives to boost the long-term viability of its gas industry and create some optimism for the country’s overall economic improvement.

Likely: Oil aside, Nigeria focuses on boosting the gas trade

The prospects for the success of the Trans-Saharan pipeline remain uncertain due to the necessity of traversing Niger, where a recent coup toppled the government and has led to a sharp turn in the country’s geopolitical alignment.

Nigeria’s final decision on the second pipeline is expected by the end of 2024; as it is supposed to traverse many countries, consensus on the project will require heroic negotiations. If successful, the African-Atlantic and West African pipeline network would become the first gas pipeline connecting West Africa and Europe.

Somewhat hedging its bet on pipelines, Abuja’s proposals also call for an expansion of the Nigeria Liquified Natural Gas facility. Europe has rapidly been increasing the number of LNG import facilities, so increasing seaborne gas exports from Nigeria appears to be an economic boost within reach.

Typically, the economics of a gas project and the potential rents arising from such a project are less attractive than those of an oil project with similar energy content. This year, Abuja will need to offer more supportive policies for investment in natural gas than were typical in negotiations for oil investments.

Possible: Nigeria’s wait-and-see approach leads to stranded assets

At current production levels, natural gas reserves in the country are estimated to last 111 years – twice the average in Africa and nearly double the expected duration of Nigeria’s oil reserves. Natural gas has also received a boost following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The European Commission has included gas under the transitional activity category of the Taxonomy Regulation. The concluding agreement from COP28 did provide additional support for natural gas. However, it fell short of explicitly naming natural gas as a “transitional fuel” to facilitate the energy transition while ensuring energy security.

The question remains whether Nigeria will take active steps now to capitalize on this low-hanging fruit to restore its economic prospects or whether investment-friendly policies will undergo further revisions, leading to more prolonged talks and delays in the implementation and pursuit of such efforts, rendering the stranded assets valueless

Global oil majors reducing operations in Nigeria

2024

Shell, one of the oldest international energy players in Nigeria, decided to exit onshore Nigerian operations and focus future investments on offshore and integrated gas operations.

France’s TotalEnergies announced its intention to exit Nigerian onshore operations. The company’s CEO Patrick Pouyanne said, “Fundamentally it’s because producing this oil in the Niger Delta is not in line with our [Health, Security and Environmental] policies, it’s a real difficulty.”

Italy’s Eni agreed to sell Nigerian Agip Oil Company Ltd (NAOC Ltd), its wholly-owned subsidiary engaged in onshore oil and gas exploration and production, along with power generation, to Oando, Nigeria’s indigenous energy solutions provider.

2022

Norway’s Equinor sold its Nigerian entity to a little-known local company Chappal Energies.

American ExxonMobil announced its intention to sell its stake in Mobil Producing Nigeria Unlimited to Seplat Energy, an independent Nigerian oil and gas company. ExxonMobil, however, maintained ownership of its deepwater assets.

Dr Carole Nakhle